Olivia Harris and Anjelique Wadlington (PC: Jo Chiang)

imagining theatre as a town hall meeting

"Theatre excels at highlighting such humanity in others, forcing us to recognize what we might ordinarily ignore. Though the contemporary national theatre scene still frequently overlooks artists from marginalized communities, many artistic directors and creators have been moving toward greater inclusion. Thinking deeper about accessibility, however, critics like Helen Shaw have suggested, “[w]e have largely given up on the idea of the writer from the street, from the battlefield, from prison, from the customs house—from anywhere other than the academy.” How can we make space in theatre for people who don’t have MFA-level polish to share their stories? One way is to pull them up from the audience."

Musical theatre can create political action, right?

Full article at The Clyde Fitch Report

"Finally, Chains Don’t Rattle Themselves dips its toe into a third niche genre, activist musical theater. The event was specifically conceived to marshal support for the Raise the Age NY campaign, which began in 2012 to end the practice of New York state prosecuting 16- and 17-year-olds as adults. Our show is part of a surge of momentum around this issue and offers direct action steps — organizations to donate to, representatives to call, future rallies to attend.

Part of me wonders whether musical theater featuring a call-to-action eliminates nuance — generally scarce in musicals as it is. Don’t we as theater makers fear our work being reduced to a message? And yet I don’t think we're simplifying the audience's journey by attempting to convince them that we should raise the age of criminal responsibility. Rather, the audience experiences something like what our composers experienced: listening to a story, confronting and bypassing their own judgments about it, walking around with it, letting it spur them to make something from it. For our composers, that “something” is a song. For the audience, collectively, eventually, it could be change."

Olivia Harris (PC: Jo Chiang)

“Chains Don’t Rattle Themselves” Finds Music in Incarcerated Youths’ Stories

Full article at The Civilians’ site Extended Play

“It was such an honor, especially because the story’s called “How Do You See Me?” and it’s about being seen. The fact that she was there and she could be seen was really powerful. And her standing there beside me as we told the story was the craziest moment! When you perform with anyone, you do something together emotionally even when there’s no words shared. There’s nothing we said about it, but being in that moment with Anjie is something I will never be able to really explain to anybody else. It’s a moment of, for me, solidarity.” - Olivia Harris

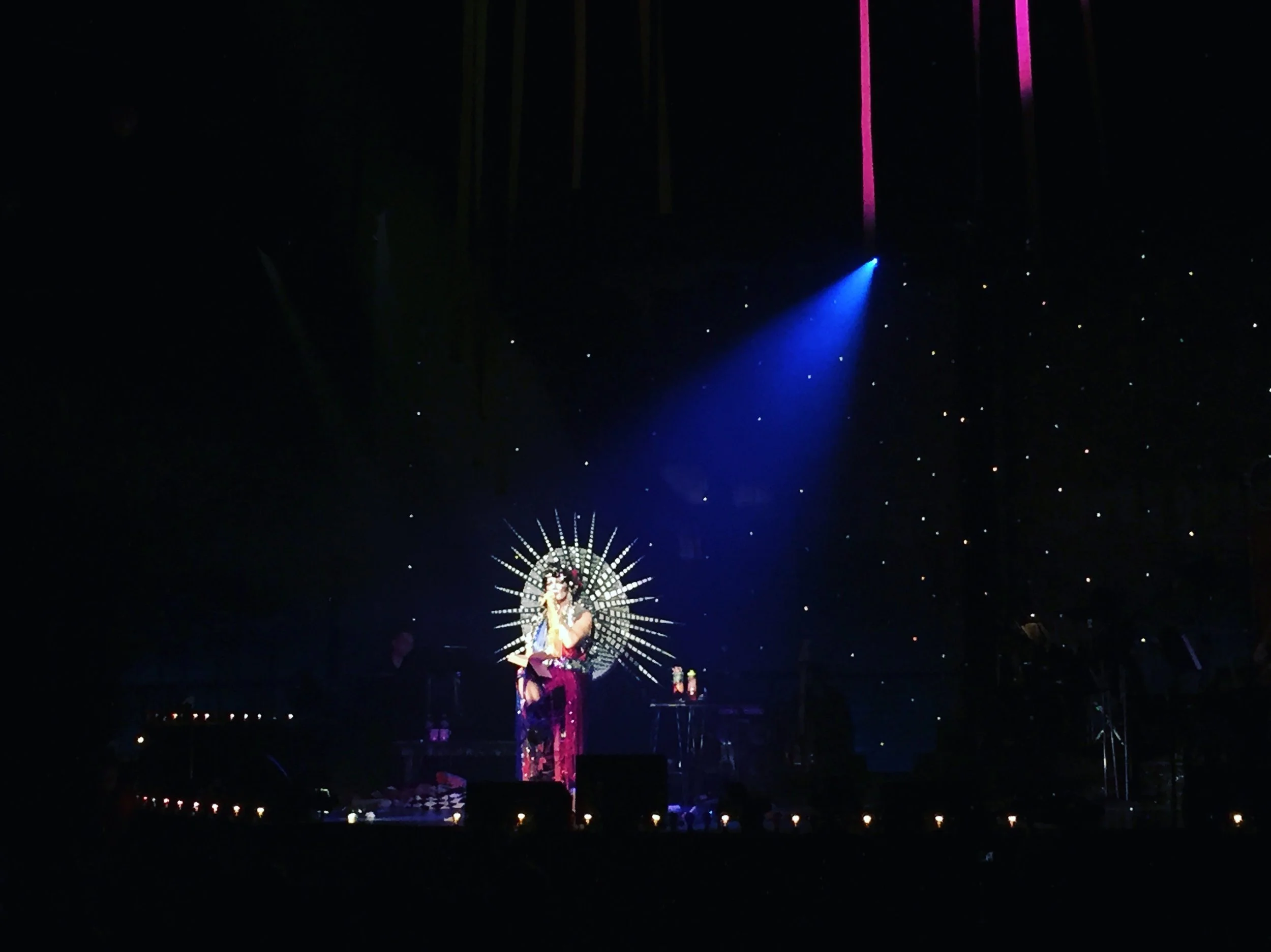

Taylor Mac

On Taylor Mac's 24 Hour, 24 Decade History of Popular Music

Early Saturday afternoon, I was comforting a stranger who had been instructed to rest his head in my lap. In the wee hours on Sunday, a partner and I danced at the gay junior prom we never had, to the tune of a Ted Nugent cover in an effort to kill him once and for all. In between, I shouted down a group of anti-WWI protesters with a few choruses of “It’s Time For Every Boy to Be a Soldier,” negotiated for land during the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889, and waited on line for (actual) soup in a Depression-era soup line, among other “shenanigans.” As a preface to most of these group activities, Taylor Mac reminded us: “It’s going to last a little longer than you want it to.”

This was a radical fairy realness ritual sacrifice (and not just our sacrifice of 24 waking hours – at one point, Mac hand-picked three men from the audience to stand on stage as a sacrifice because unfortunately, though judy allowed that they might be amazing people, they had come dressed as the Patriarchy).* It was a survey of American history that placed the marginalized front and center. “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” an English song mocking the effeminacy of Americans, was reframed as an act of dandy revenge. Three hours (decades) were devoted to a workshop of a heteronormative colonialist Broadway musical/future Oscar-winning film about 19th century Irish immigrants, a segment that ended with the central couple’s adopted two-spirit Native American daughter rebelling and striking out toward an unknown future. The turn of the 20th century segment took place in the Jewish tenements, while the 90s were devoted to radical lesbian Riot grrrl punk songs.

Mac was the tireless star, writer, co-director, and conceiver (or maybe the conceived? Late in the show, a hanging “womb” set piece descended over Mac and became a final costume in a stunning transformation). Even more, judy was ringleader, puppeteer, high priestess, spiritual leader. As such, decrees were handed down: perfection is for assholes. Don’t equate your equality with your ability to shop. Everything you’re feeling is appropriate. And yet, if this was judy’s own microcosmic vision of American society, judy rejected hierarchy and the global capitalist society that relies on it. Judy insisted that the intention was not to teach, but simply to remind us of things we had forgotten or buried, or that others had buried for us.

Mac was in a way a canvas, dressed in and then stripped of a series of 24 elaborate tacky/gorgeous gowns that vomited the given decade’s iconography onto judy’s body, created by costumer Machine Dazzle. Machine was foregrounded as an equal artist in the creation of the work, even serving as Mac’s on-stage dresser. Other collaborators granted major credit and time in the spotlight included Matt Ray, the intrepid musical director and arranger of all 246 songs; James Tigger! Ferguson, fearless stripperformance artist; the Dandy Minions, individuals who guided the audience, brought out meals, and kept the party going; plus the musicians, back-up singers, puppeteers, acrobats, burlesque performers, marching band players, chorus singers, designers, random on-stage knitters, and us, the audience.

Particularly moving was an audience participation moment in the final hour, during an original song Mac wrote about the Pulse nightclub shooting – judy directed us to embody, with a pose or a gesture, the various types of people at the club that night, with no mention of the eventual violence. Brought to life during the sleep-deprived 11am hour on Sunday, this was both the enactment and re-enactment of a community building itself up as it was falling apart. It was the people of October 9th trying to reaching back to those of June 12th, to the crowd gathered at the AIDS Memorial Quilt in San Francisco in 1987, to the inhabitants of every moment of time in American history when the oppressed thought not of granting forgiveness to their oppressor, nor of the shame that others were projecting onto them, but of the urgent need to see each other.

During the inevitable, prolonged standing ovation at the end of the show (and there had been many already, including one for a haunting “Soliloquy” from Carousel during the 40s section), the audience honored Taylor Mac and judy’s collaborators. At the same time, I think, or hope, we weren't just celebrating the creators, as judy had warned against at the start of the show, but the act of creation. Not the (glorious, exhausted) nouns, but the verb.

*Taylor Mac’s preferred gender pronoun is judy, and at one point judy explained, hilariously, that one of the reasons for it is that no one can say “Taylor’s preferred pronoun is JUDY,” rolling their eyes with distaste, and not sound campy.